Overarching Aims, Duties and Principles

1. The Aims of Adult Safeguarding

The aims of adult safeguarding under the Care Act are both reactive and proactive as follows:

- To prevent harm and reduce the risk of abuse or neglect to adults with Care and Support needs;

- To stop abuse or neglect wherever possible;

- To safeguard adults in a way that supports them to make choices and have control about the way they want to live;

- To promote an approach that concentrates on improving life for the adult (s) concerned;

- To raise public awareness so that communities as a whole, alongside professionals, play their part in preventing, identifying and responding to abuse and neglect;

- To provide information and support in accessible ways to help people understand the different types of abuse, how to stay safe and well and what to do to raise a concern about the safety or Wellbeing of themselves or another adult; and

- To address what has caused the abuse or neglect.

tri.x have developed a flow chart of the Safeguarding Adults Overall Process, which can be used alongside this procedure. See Safeguarding Adults Overall Process.

2. The Statutory Duty to make Enquiries

The safeguarding duty

The Section 42 statutory duty to make enquiries (or cause enquiries to be made) applies when all the following criteria are met:

- The adult has needs for Care and Support (whether these have been assessed or are being met by the local authority or not); and

- They are experiencing, or at risk of experiencing abuse or neglect; and

- As a result of Care and Support needs they are unable to protect themselves against the risk of, or the experience of, abuse or neglect.

Note: An adult is a person aged 18 or above.

Guidance on establishing whether the duty is met

1. The adult has needs for Care and Support

When considering whether the adult has needs for Care and Support, it does not matter whether their needs have been formally assessed or not (or which agency has carried out the assessment. Neither does it matter who is providing or commissioning any care and support services.

For example:

- Services commissioned by adult Care and Support;

- Services commissioned by children's services (e.g. a 0-25 team or education services);

- Services commissioned or provided by the NHS (e.g. in a hospital or through NHS Continuing Healthcare);

- Support from an informal carer (such as a family member or friend); or

- Services arranged outside of adult Care and Support (for example privately arranged services or those provided by a faith or charity organisation).

There are 10 areas of potential need (outcomes) set out in the Care Act:

- Manage and maintain nutrition;

- Maintain personal hygiene;

- Manage toilet needs;

- Being appropriately clothed;

- Be able to make use of their home safely;

- Maintain a habitable home environment;

- Develop/maintain family and other personal relationships;

- Access/engage in work, training, education or volunteering;

- Make use of community services;

- Carry out caring responsibilities for a child.

Examples of adults who may have a need for Care and Support could include:

- An older person;

- Someone with mental health needs, including dementia or a personality disorder;

- A person with a long-term health condition;

- Someone who misuses substances or alcohol to the extent that it affects their ability to manage day-to-day living.

Consideration of this need for care and support must be person-centred (for example, not all older people will be in need of care and support but those who are 'frail due to ill health, physical disability or cognitive impairment' may be). The need for Care and Support should be considered alongside the impact of needs on the adult's individual wellbeing.

If there is reasonable cause to suspect that the adult has needs for care and support then this condition should be deemed as met.

2. The adult is experiencing, or at risk of experiencing abuse or neglect

Organisations and individuals should not limit their view of what constitutes abuse or neglect, as it can take many forms.

Responses and decisions should be based on the specific circumstances and take into consideration the actual or potential impact on the adult's individual wellbeing, together with their view on the impact that the abuse or neglect has had upon them.

The Care Act 2014 sets out 10 specific categories of abuse and neglect.

For information about these categories, and examples of how the accompanying abuse or neglect may be experienced, see: The Care Act 2014, Categories of Abuse and Neglect.

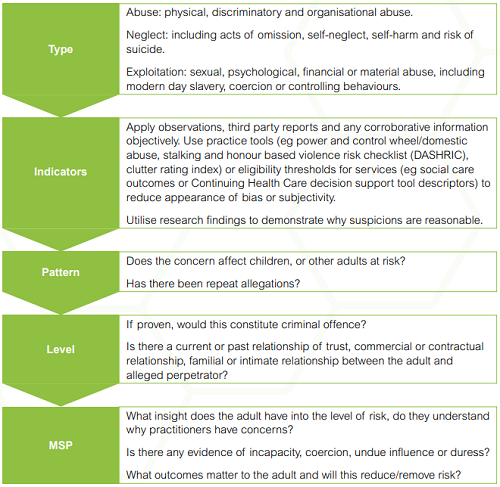

The diagram below sets out factors that might be considered in making the necessary judgements about 'reasonable cause to suspect'; and whether the situation reflects the statutory criteria:

Diagram source: Making decisions on the duty to carry out Safeguarding Adults enquiries (Local Government Association).

3. As a result of Care and Support needs, the adult is unable to protect themselves against the risk of, or the experience of, abuse or neglect

Potential barriers to an adult's ability to protect themselves might include:

- They do not have the skills, means or opportunity to self-protect;

- They may have a disability which impairs their capacity to make decisions about protecting themselves or may need support to enact decisions;

- They live in a group setting where they lack control over the way they are treated or the environment;

- There is a power imbalance;

- They may not understand an intention to harm them;

- They may be trapped in a domestic situation which they are unable to leave, or where coercion and control means they cannot make a decision about doing so;

- Their resilience and resourcefulness to protect themselves from harm is eroded by, for example, coercive control and / or a high risk environment.

Vulnerability

An adult's vulnerability is determined by a range of interconnected factors, including personal characteristics, factors associated with their situation or environment and social factors.

Some of these factors are described below:

| Personal Characteristics of the adult that may increase vulnerability may include: | Personal Characteristics of the adult that may decrease vulnerability may include: |

|

|

| Social/situational factors that increase the risk of abuse may include: | Social/situational factors that decrease the risk of abuse may include: |

|

|

3. The Duty to Promote Wellbeing

The duty to promote Wellbeing

Wellbeing is the single most important concept of the Care Act. The duty to promote individual Wellbeing applies at all times; in every single process, conversation or decision that is made and you must be able to demonstrate that you have done so.

Promoting Wellbeing means actively seeking improvements in aspects of Wellbeing when carrying out any care and support function. This includes safeguarding.

There are 9 Wellbeing domains:

- Personal dignity;

- Physical or mental health;

- Protection from abuse and neglect;

- Control over day to day life;

- Participation in work, education, training or recreation;

- Social and economic Wellbeing;

- Domestic, family and personal relationships;

- Suitability of living accommodation;

- Contribution to society.

Under the Care Act the Wellbeing domains are all as important as each other. Any hierarchy can only be determined or described by the adult whose Wellbeing it is. This means that, even though the process is safeguarding, the 'Protection from abuse and neglect' Wellbeing domain may not be the most dominant area of concern for the adult.

It is vital that you understand your duties in relation to promoting individual Wellbeing. See: The Care Act 2014, Promoting Individual Wellbeing.

What you must establish about Wellbeing

As part of the safeguarding process, you must understand:

- Which areas of Wellbeing are most important to the adult at that moment in time;

- Which areas of Wellbeing are least important at that time;

- Whether there are other areas of the adult's life important to them but not listed as a domain (the domains under the Act are not definitive as Wellbeing is personal);

- Which areas of Wellbeing are causing the adult concern or worry;

- What impact any concern or worry is having (or could have) across the Wellbeing domains (is there a destabilising effect?); and

- How the adult thinks any Care and Support needs interact and impact on Wellbeing.

How safeguarding practices can promote Wellbeing

- Always assume that the adult is best placed to judge their own Wellbeing;

- Enable the adult to participate as fully as possible in the process and in decision making;

- Always seek and take into account the views, wishes and feelings of the adult before making any decision or taking any action;

- If a person is unable to express a present view, wish or feeling always take into account any past views, wishes or feelings they have expressed;

- Ensure that decisions made have regard for the things that are important to the person and are not based on assumptions, preconceptions or judgements;

- Never advocate risk management measures that do not take account of individual Wellbeing;

- Work together with other professionals to ensure Wellbeing is promoted throughout the safeguarding process;

- Work to achieve a balance between the Wellbeing of the adult and the Wellbeing of any other adults with care and support needs, or any carers;

- Minimise restrictions on individual rights or freedoms of the adult.

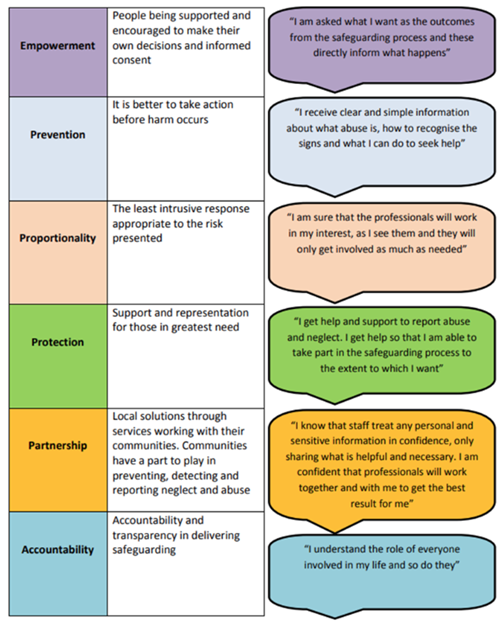

4. The Six Key Principles of Adult Safeguarding

The Care Act statutory guidance defines 6 principles that should underpin all safeguarding functions, actions and decisions:

- Empowerment – People being supported and encouraged to make their own decisions and informed consent;

- Prevention – It is better to take action before harm occurs;

- Proportionality – Proportionate and least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented;

- Protection – Support and representation for those in greatest need;

- Partnership – Local solutions through services working with their communities. Communities have a part to play in preventing, detecting and reporting neglect and abuse;

- Accountability – Accountability and transparency in delivering safeguarding.

The principles apply to all sectors and settings including care and support services, commissioning, further education colleges, welfare benefits, housing, regulation and provision of health and care services, social work, healthcare, wider local authority functions and the criminal justice system.

Each principle is accompanied by its own 'I' statement clearly explaining what the principle would feel like in action to an adult affected by safeguarding. Often the principles are referred to solely as 'I' statements.

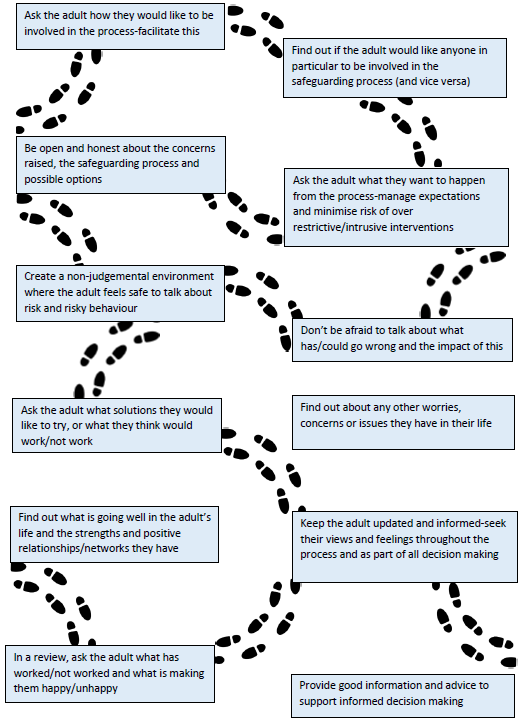

5. Making Safeguarding Personal

Making Safeguarding Personal (MSP) is an approach to safeguarding that is person-led and outcomes-focused.

It is about having conversations with adults about how responses to safeguarding situations can be made in a way that enhances their involvement, choice and control as well as improving their quality of life, well-being and safety.

It is about seeing adults as experts in their own lives, and working alongside them to identify the outcomes they want.

It focuses on achieving meaningful improvements to adult's lives to prevent abuse and neglect occurring in the future, including ways for them to protect themselves and build resilience.

It recognises that individuals come with a variety of different preferences, histories, circumstances and life-styles; so safeguarding arrangements should not prescribe a process that must be followed whenever a concern is raised, but instead take a more personalised approach.

Making Safeguarding Personal is firmly embedded in the statutory guidance for the Care Act 2014 and is an approach that should flow through every aspect of adult safeguarding, not just formal enquiries.

Some ways to Make Safeguarding Personal

As part of Making Safeguarding Personal, all agencies involved should also ensure that the adult at risk is not placed at any disadvantage during any part of the process because of a protected characteristic (an anti-discriminatory approach).

This includes, but is not limited to:

- Identifying whether the adult at risk is likely to experience any difficulty engaging in the safeguarding process because of a protected characteristic, and then putting appropriate measures in place to facilitate and maximise their engagement.

- Sense checking decisions made to ensure that the rationale is not based on an assumption relating to a protected characteristic.

- Supporting adults at risk to access local community services that support those with a protected characteristic (for example LGBT+ or older adult) services.

Making Safeguarding Personal in XXX (insert name of customer)

Insert local information as required

MSP wider resources

There are a wide range of resources that have been developed by a number of trusted organisations to support effective implementation of the Making Safeguarding Personal approach into practice. These resources can be found in the dedicated section of the Contacts and Practice Resources area.

6. Information Sharing

Effective sharing of information between practitioners and local organisations is essential for early identification of need, assessment and service provision. Safeguarding Adult Reviews have consistently highlighted that missed opportunities to record, understand the significance of and share information in a timely manner can have serious consequences for the safety and wellbeing of adults at risk. The Data Protection Act 2018 and UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are not barriers to collating and sharing information but provide a framework to ensure that personal information about living persons is shared appropriately.

6.1 The 7 Golden Rules of Information Sharing

The 7 Golden Rules of Information Sharing are set out in the Department of Education guidance, Information sharing: Advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services for children, young people, parents and carers. Whilst this guidance is for those involved in safeguarding children, the 7 Golden Rules apply equally when working with adults at risk. The rules below have therefore been adapted as such:

- All children and adults at risk have a right to be protected from abuse and neglect. Protecting them from harm takes priority over protecting their privacy, or the privacy rights of the person(s) failing to protect them.

- When you have a safeguarding concern, wherever it is practicable and safe to do so, engage with the child (and/or their carers)/ adult at risk, and explain who you intend to share information with, what information you will be sharing and why.

- You do not need consent to share personal information about a child/adult at risk or anyone else if the child/adult at risk is (or could be) at risk of serious harm.

- Seek advice promptly whenever you are uncertain or do not fully understand how the legal framework supports information sharing in a particular case.

- When sharing information, ensure you and the person or agency/organisation that receives the information takes steps to protect the identities of anyone who might suffer harm if their details became known (this could be the child/adult at risk but could be a carer, family member, neighbour or colleague).

- Only share relevant and accurate information with individuals or agencies/organisations that have a role in safeguarding and/or providing the child/family or adult at risk with support, and only share information they need to support the provision of their services.

- Record the reasons for your information sharing decision, irrespective of whether or not you decide to share information.

6.2 The Caldicott Principles

The Caldicott Principles apply to the use and sharing of confidential information within, with or by health and social care organisations.

Principle 1: Justify the purpose(s) for using confidential information.

Principle 2: Use confidential information only when it is necessary.

Principle 3: Use the minimum necessary confidential information.

Principle 4: Access to confidential information should be on a strict need-to-know basis.

Principle 5: Everyone with access to confidential information should be aware of their responsibilities.

Principle 6: Comply with the law.

Principle 7: The duty to share information for individual care is as important as the duty to protect patient confidentiality.

Principle 8: Inform patients and service users about how their confidential information is used.

7. Principles of the Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 is a comprehensive statutory framework that:

- Protects the autonomy of people who have capacity to make their own decisions; and

- Protects people who lack capacity, by ensuring that they are always involved in decisions relating to them, and that any decisions made on their behalf are made in the right way.

The Mental Capacity Act applies whenever:

- There are doubts over the ability of any person (from the age of 16) to make a particular decision at a particular time; and

- The person has an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain.

The Mental Capacity Act does not apply when:

- There are no concerns or doubts about the person's mental capacity; or

- The person does not have an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain.

Everyone working with (or caring for) any person from the age of 16 who may lack capacity must comply with the Act and its 5 statutory principles.

If the principles are not clearly applied any decision that is subsequently made on behalf of a person who lacks capacity is not lawful.

| Principle | In Practice | |

| 1 | A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity. | Every person from the age of 16 has a right to make their own decisions if they have the capacity to do so. Practitioners and carers must assume that a person has capacity to make a particular decision at a point in time unless it can be established that they do not. |

| 2 | A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him to do so have been taken without success. | People should be supported to help them make their own decisions. No conclusion should be made that a person lacks capacity to make a decision unless all practicable steps have been taken to try and help them make a decision for themselves. |

| 3 | A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he makes an unwise decision. | A person who makes a decision that others think is unwise should not automatically be labelled as lacking the capacity to make a decision. |

| 4 | An act done or decision made, under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in his best interests. | If the person lacks capacity any decision that is made on their behalf, or subsequent action taken must be done using Best Interests, as set out in the Act. |

| 5 | Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person's rights and freedom of action. | As long as the decision or action remains in the person's Best Interests it should be the decision or action that places the least restriction on their basic rights and freedoms. |

For further guidance about the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and how to apply the principles effectively see: The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Resource and Practice Toolkit.

8. Ensuring Aims, Duties and Principles are applied

All of the overarching aims, duties and principles of safeguarding apply at every stage and whenever any decision is made or action taken.

It is therefore essential that decision makers have regard for them before any decision is made (or action taken) and also in the review of any decisions or actions (either as part of the safeguarding process or case audit).

Conversations regarding aims and principles should be clearly recorded in line with local recording requirements.